Please enjoy this extended interview with Alex Frayne, acclaimed photographer of the banal and unembellished. Alex has a comforting, almost nostalgic way of documenting people going about their lives and of ordinary, every-day stuff. I appreciate Alex’s deep focus and attention to a subject or series, and commitment to photographing the world as it is.

I highly recommend that you check out his portfolios at www.fusionjazzer.com and his Instagram page @alex.frayne. His books Adelaide Noir and Theatre of Life are also available for purchase. Thanks Alex!

1) Describe your style, are you inspired by any type of photography or specific photographers?

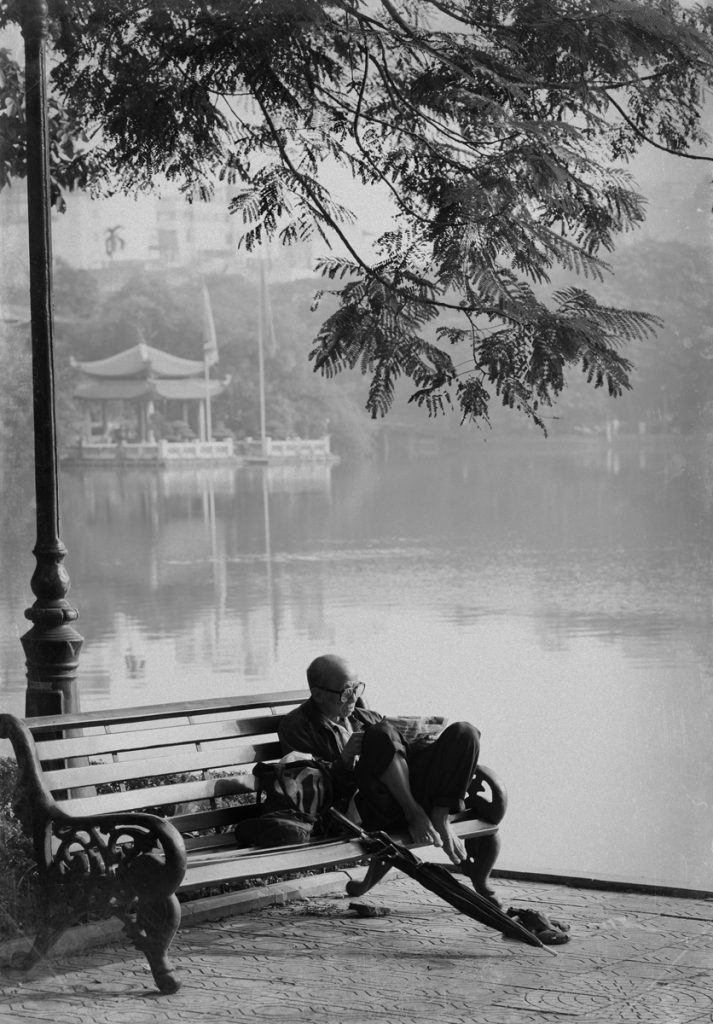

My style has its pedigree in cinema, as that area comprised my formative years as a student of Screen Studies at Flinders Uni (BA). So I have a keen sense of mise-en-scene and montage and this is underpinned with the realisation that while cinema is not stills, the two forms have common ancestry in tropes of lighting, framing, mood, tone and drama.

So it comes as no surprise that I reference or at least derive a style more in common with filmmakers rather than other still photographers. I like Pressburger, Roeg, Eastwood, Malick and many, many others, including the stills photographers Diane Arbus and Vivienne Meyer.

Despite the canon of works before me though, I rarely think of these pioneers nowadays – really, I’m just keen to instigate unique work that people can recognise, I don’t give two hoots about past greats.

2) What message do you want people to come away with when they look at your images?

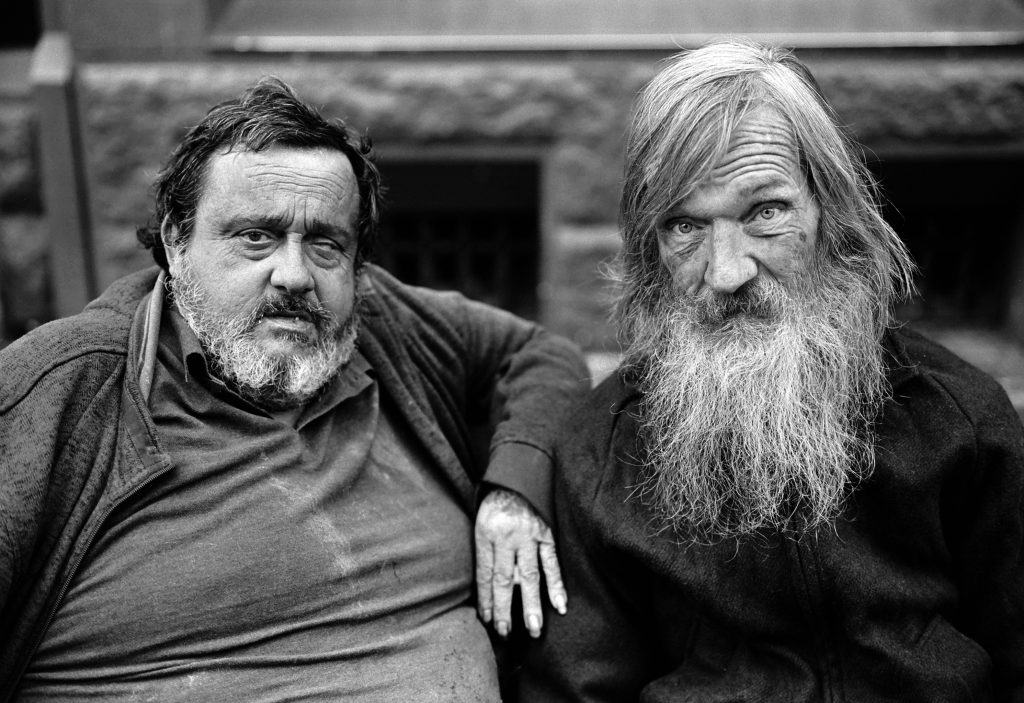

I’m not into messages, although my series OVERSEERS OF STREETS has been running for a year or more now; this series aims to bring powerful images of homeless people onto the feeds of the well off – meaning, I suppose, that there is a strong element of social awareness being dealt out and this will inevitably provide a message.

With my other work, now represented in two books, it’s less about message and more about power. That is, the power of the image regardless of its relationship to societal trends, movements, or hashtags.

I’m less interested in message and more interested in mood, tone, scale, joy, melancholia – old fashioned stuff like that.

3) What motivates you to take photographs, even when you’re unmotivated?

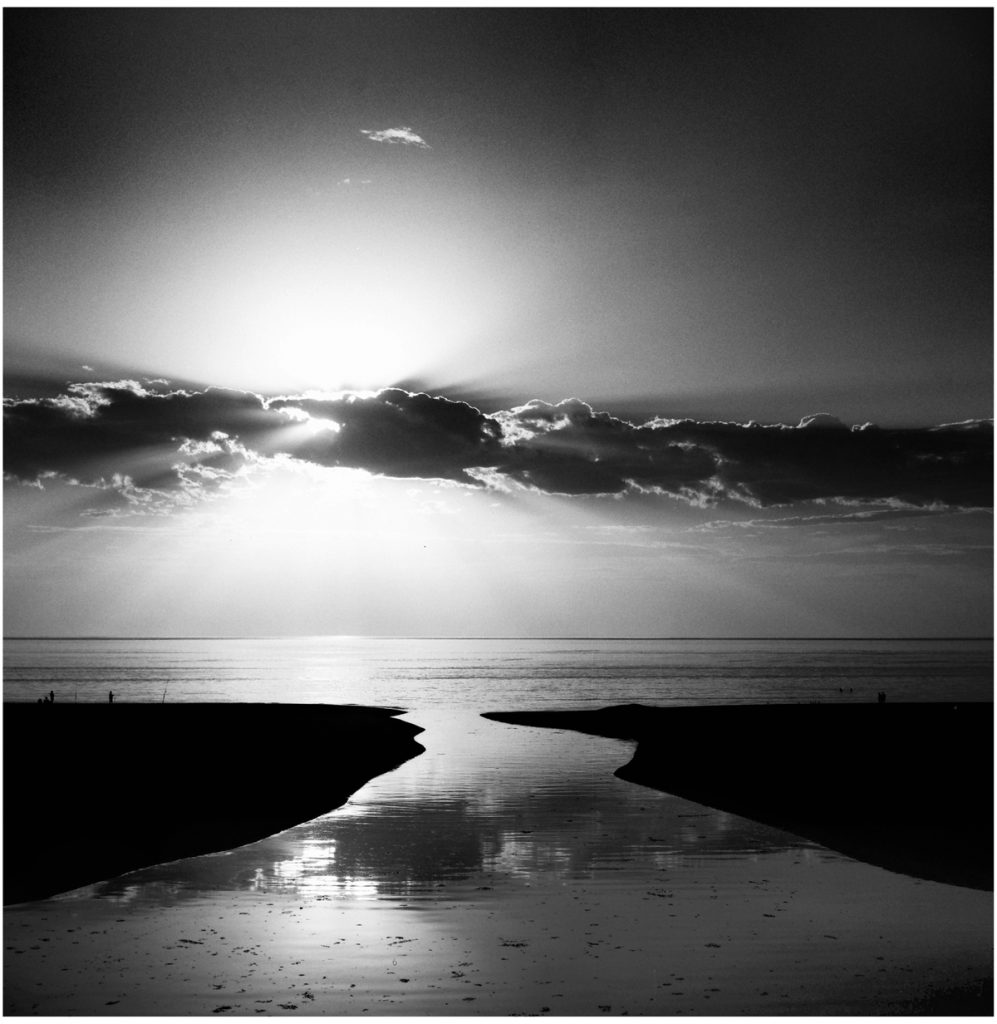

I’m always motivated to take photographs! One of the big motivators is light. I NEVER shoot during the middle of the day, so it’s up early and out late for me – that is the schedule – particularly shooting on film rather than digital – I only shoot analogue, so why waste money on frames when the light is less than ideal?

Money is also a motivator. My work is commercial and collected, and I normally only do editions of one. So when new work is sold, there is a need to keep shooting new work because I don’t have the luxury of allocating “editions.”

4) What is your favourite location/image and why?

“The world” is my favourite location – I travel o/s regularly and am constantly awed by the diverse array of people and place for my lens – but in terms of a favourite local location, it would be The Mallee – I’m shooting an ongoing series of images of that region in all its glorious flatness and optimism.

Bereft of high rainfall, the Mallee is a place of constant photographic richness and also a source of Depression Era bleakness and 21st Century technology.

5) What is one piece of your kit that you couldn’t do without?

I think my Fuji GW2 medium format camera is the winner there. It shoots 6x9cm 120 film frames with a fixed 90cm lens. Rangefinder all the way and no frills in a very Japanese way. Double cranking and it’s built like the proverbial brick shit-house.

6) What has been your biggest struggle with photography so far?

I think the struggle is again about boring old light. South Australia, blessed with the greatest canvas in the world, is home to the poorest daytime light in the world. Mongolia has the most days of sunny light in the world. Surely South Australia has the second worst statistic there. In summer it is piercing, everlasting and brutal.

So the challenge is finding a way through that practical difficulty. Another struggle is to with aesthetics. The forming of a recognisable aesthetic is the hardest artistic challenge and involves quite a bit of work.

Aesthetics has a lot to do with how you view the world, and also how you see yourself. Without this knowledge, you can not lay claim to an aesthetic.

90% of photographers have zero aesthetics in their work. Their work is passive and reactive rather than aggressive and probing. Passivity is the enemy of aesthetics, but it is very common because of the way images are now presented on screens. It necessitates a passivity which is appropriated by artists. It is the road to oblivion for an artist.

Many film-makers also have no aesthetics to speak of – i.e. it’s impossible to determine that the same hand is behind two separate works. When I was a teenager I subscribed to DOWN BEAT magazine, which was and is the jazz music magazine from the USA.

At the back of the magazine was the “blindfold test.” Musicians would be played 10 recordings by famous jazz artists and they had to identify those musicians after hearing the songs.

Mostly, the subject could indeed identify the creators of those songs because each song has such a strong aesthetic. Miles Davis, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Allan Holdsworth – all of their songs were instantly recognisable after a single playing of their material.

7) I notice that you like to take photos of the smaller, more ordinary subjects that most people probably pass by. This is an area that I’m delving into myself, so I’m curious to know what it is about those sort of subjects that inspires you to photograph them?

It has a lot to do about curiosity and the desire to record the aftermath or residue of humanity. Big events, wars, famines and catastrophes happen in the world and will be covered by various media and we will see those images on the internet, or indeed we may be caught up in those events.

But daily, hourly, and minute by minute in most people’s lives are the occurrences which often go unnoticed, unexplained and unremarked upon. These small events contain the elements of drama, tragedy and comedy that are felt by those who are involved in those seemingly insignificant events.

8) The idea of a project, or series of images, is appealing to me and I’m sure many others. What do you see as the benefits of a project, and should every serious photographer start, and importantly finish one?

Yes I think the notion of a series is one that brings a certain structure and logic to the entire collection. I think there is a requirement in any artistic pursuit which is the in-depth, closer look at any given subject, thing or notion.

This begins with a certain curiosity, or ‘problem’ that you feel needs to be examined and better understood through your art form. The curiosity can then be solved through the constant, relentless pursuit of a certain ‘truth’ that is revealed through the art form.

This ‘reveal’ will be intrinsically linked to the art-form (photography) and unique to it.

A key example would be my MALLEE SERIES. The question I address in the work has to do with the inherent difficulty of eeking out an existence, as farmers do, out there in an inhospitable environment (the land east of the Murray River).

In a practical sense, defining the ‘work as series’ does serve another important function and that is to guide people who buy and collect the work; they often will ask about new work in the context of a series in which they are invested through prior purchases.

9) I thoroughly enjoyed your series The Overseers of Streets, which feature images of Adelaide’s homeless community. How do you go about building rapport with your subjects? Must a balance be struck between your requirements as a photographer and the needs of the homeless?

With regards to the series known now as THE OVERSEERS OF STREETS – well that body of work came off the back of my book THEATRE OF LIFE (2017), as well as the campaign to halt the demolition of Royce Wells’s house in Fullarton. I wanted to test the power of photographic art to effect social change.

A picture of the man taken last year went viral, even the UK press picked up on it – and a crowd funding campaign ensued that has seen the issue with Wells’s house resolved. I was approached then by some people who work for the Anti-Poverty Network (APN).

They discussed the use of my images of homeless people and I allowed those images to be used for their “IT’S TIME” campaign to raise the NewStart allowance.

A short film was then produced by some volunteers which served as a visual “backdrop” for the APN choir who remixed the famous 1972 Whitlam campaign song to suit their plight. Awareness was then raised about this pressing issue of our time (poverty).

So those images exist as part of a social context and the subjects are willing to be involved, because ultimately it’s in their own interest to do so.